In my last post, I raised the question of whether higher ed being stuck halfway through the transition to high-quality, high-engagement blended learning may contribute to college retention problems and, therefore, to the drop in total enrollments we’ve seen. (For more exploration of this question, check out the recent EdSurge article “As Student Engagement Falls, Colleges Wonder: ‘Are We Part of the Problem?’”) Then I explored an example of a learning design of an Argos-hosted “courseware” product that shows how digital learning experiences can be designed and continuously tuned to foster meaningful student engagement with learning.

In this post, I’ll explore how the current EdTech ecosystem almost forces educators working with technology to spend much of their time on low-value work and makes it hard for them to focus on high-value work that would keep students more engaged with learning.

An 80/20 Rule of Teaching

When preparing to teach a new course, many instructors want to adopt curricular materials covering a substantial percentage of the course (particularly in survey-level courses). Let’s consider it roughly 80% of the course coverage, although it might be higher or lower in individual cases. They want to focus their time on preparing the other 20%(ish). Maybe they need to adjust the course to the needs of their student population or their program. Maybe they have particular expertise to bring to their teaching, a project they like to have students do, or some other twist that lets them add value through their personal strengths. In other words, they want to put as much of their time as possible into the parts of the course design where they think they have the most to add and as little time as possible into the rest. This was one of our founding hypotheses at Argos. Since we started a year ago, we’ve conducted multiple market research studies, including two run by independent parties, and talked with many prospective customers. All of these research efforts strongly confirm our hypothesis.

To further complicate the situation, educators aren’t really dealing with an 80/20 problem so much as a 60/20/20 problem, where the other 20% is the holes in their adopted content that they wish were covered a certain way but aren’t. So they have to either create new content, find it on the web, or perform some combination of the two. Again, our research bears this out. Educators strongly resist teaching an adopted curricular product with no modifications. Even the ones who have mandates to do so, and think they do so, don’t. They will search the web for supplemental content or create their own. They don’t think of this as adapting or working around the curricular product. But it is.

What has EdTech offered to solve this problem? From the courseware platform category, we got empty containers, each designed to support a specific pedagogical approach. The fancier these products were, the more rigid they were because building a platform that is both adaptive and flexible is incredibly hard. Empty courseware platforms—especially ones that dictate pedagogy—solve the wrong problem for educators. Creating courses out of whole cloth or little tiny bits strewn across the internet does not help educators meet their 80/20 goal. That’s one major reason why almost every courseware platform provider we know of started creating a catalog of content shortly before they were sold off in a fire sale or went out of business.

In the proprietary textbook market, most digital textbook replacements are sold—or rented—as PDFs. Even the more full-featured products are limited in the amount of customization they allow to instructors. Instead, many of the digital content options educators have are so locked down that they might as well be analog textbooks.

So how must an educator with a 60/20/20 problem manage this situation? What does that look like? For starters, their LMS syllabus page is littered with directions like this:

Week 3

- Read chapter 7.0 – 7.2 in your textbook PDF.

- DO NOT READ 7.3-7.5. Instead, go to this folder and read the PDF titled “Alternate 7.3 – 7.5”.

- Follow the first link at the bottom of that document labeled “Virtual Lab” and take the lab there. (Don’t worry that the web page has a different university’s name on it. You’re in the right place.)

- Navigate back to the PDF and follow the second link to the quiz in the LMS.

- Go back to your textbook PDF and read chapter 7.6 – 7.8.

Think about the labor involved before the educator can write those directions. How much time does it take to create and organize all that content? How much of that time is spent on educationally high-value work? And, by the way, what are the chances that some students will get lost or fail to follow the directions properly?

Of course, if the content were editable, that would help. So OER should solve this problem, right?

For the most part, it hasn’t so far. While the license to edit helps in theory, OER textbooks are most commonly used in the form of PDFs or non-editable web pages. This may be one reason why a recent doctoral dissertation found that many faculty treat OER they adopt as static and unchangeable. (See the final chapter of the dissertation for details.) So you are almost as likely to see directions like those above in a class that uses an OER digital product as in one that uses proprietary course materials.

We at Argos believe there is a better way.

The Right 80, the Right 20

Unlike the courseware platform vendors, Argos launched with a catalog of titles on Day 1. We expect to have at least 100 titles, including the entire OpenStax catalog, available on the platform by next year. Not all of these titles will have OER licenses. But we encourage even proprietary publishers on Argos to at least grant permission for educators to edit the content for their classes and academic departments.

If educators adopt products that give them license to edit, then they can do so right in the platform. Want to replace the existing chapter 7.3 – 7.5? Don’t create a separate document and spend half a day setting up the navigation in your LMS. Just replace the publisher content with your own.

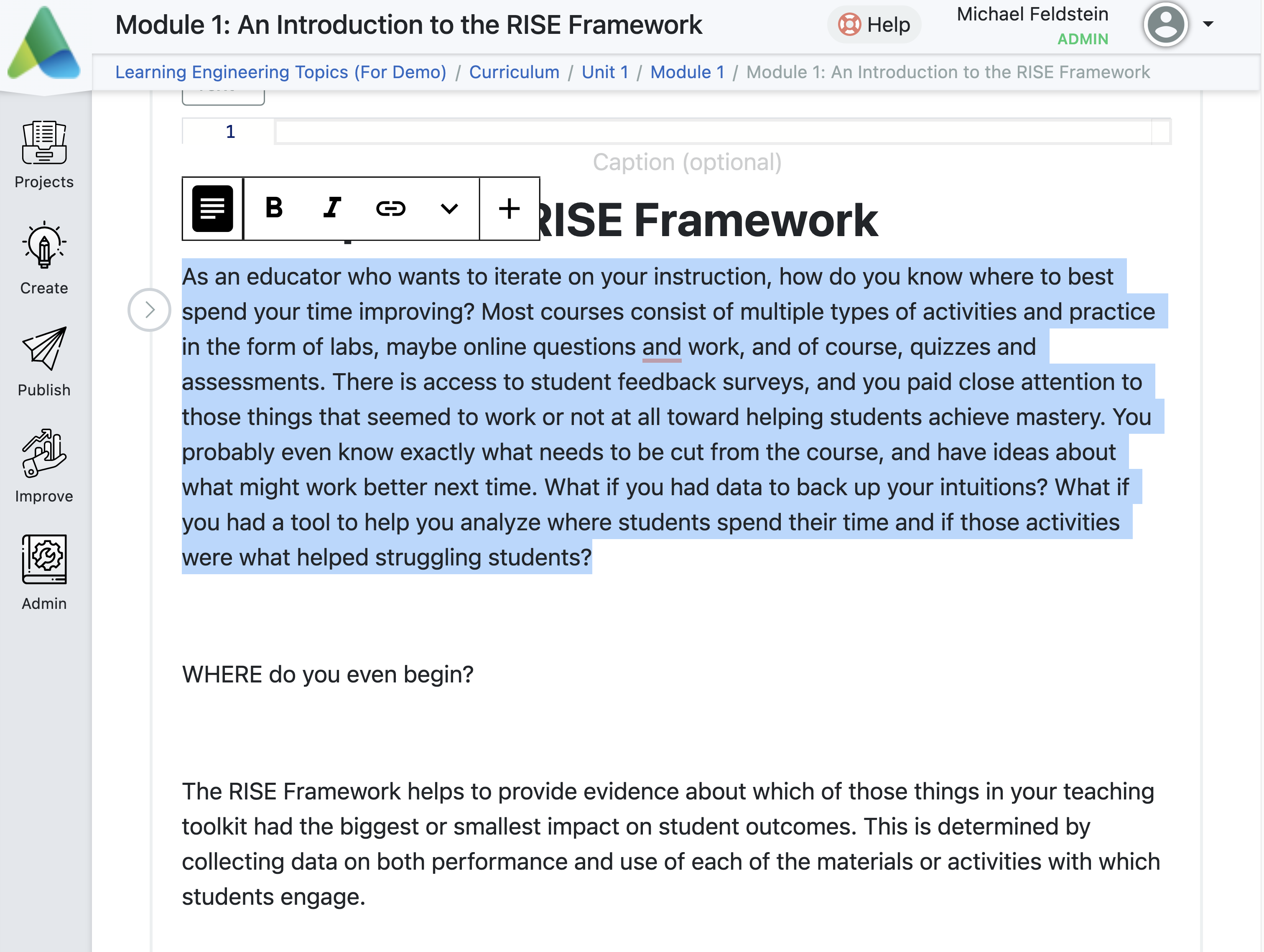

In my last post, I spent some time showing off our adaptive editor that enables the creation of very complex, rules-based learning experiences. Here’s a peek at the core editor, which is still quite rich in its capabilities while emphasizing simplicity that supports easy creation and editing of content:

Want to add a quiz or activity? Add it right where it should be, next to your content.

As you can see, this editor is intentionally similar to other web editors you’ve used inside your LMS or on a web publishing platform like WordPress. We’re working hard with our open-source development partners to continue making the editor both easier to use and richer at the same time. (This is almost as important for publishers as it is for content adopters.)

Some of what I’m describing here may not appear unique or revolutionary. Others have built marketplaces of content and included content editing capabilities. But in addition to coming to market with a large and rich catalog of editable products, we are seeking to combine power and simplicity in ways that open up new possibilities.

Engagement is in the Details

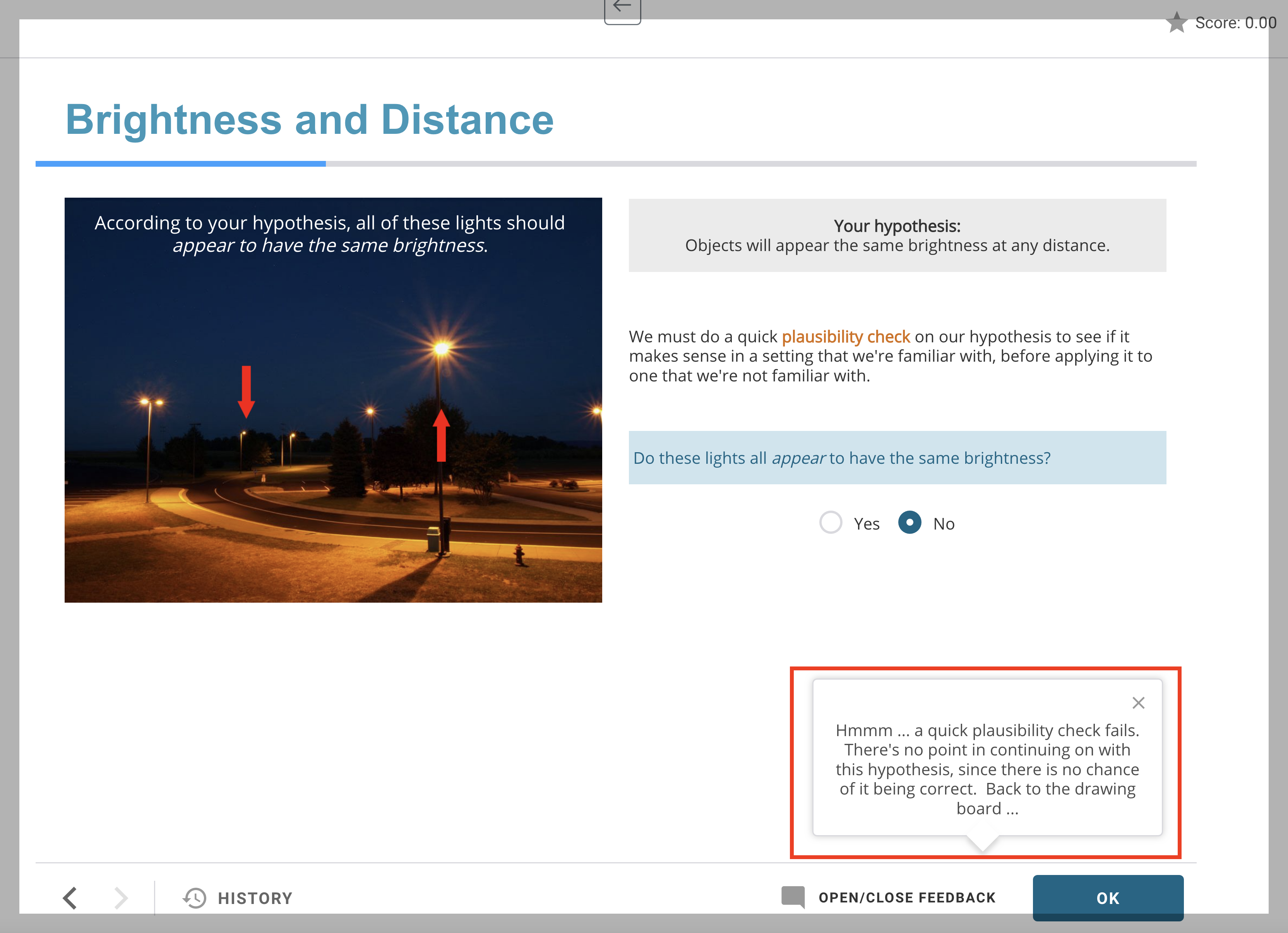

Let’s return to an example of a design bit from my previous post. Recall that students were learning about how the distance of a star affects its brightness. The lesson started not with text or explanatory video but with a thought question:

In a typical multiple-choice question, students might be just scored with no feedback, told they were wrong and given a chance to try again, or given a hint and a chance to try again. How closely does this resemble what might happen in an actual classroom or tutoring session with a human educator?

Before we answer, let’s back up one step and examine the educator’s opening move. Not a lecture but a question. A puzzle. Can you remember an educator you had who would toss a puzzle to the class instead of launching into a lecture? Can you remember how you felt about it? This is a common teaching move. In fact, many textbooks provide discussion questions for educators to pose just such a puzzle to the class…before launching into a much more lecture-like discursive mode. This was somewhat necessary in the era of paper products. There’s a limit to how far quasi-rhetorical questions on a printed page can take students. But with digital curricular materials, it’s possible to weave active learning into the self-study portion of the class.

In our astronomy example, suppose the first answer a student tries is wrong. What would the educator do? If it’s in a class, she might solicit other answers from the group. In other words, she’d let the class chew on the question and see if they could figure it out together. If it’s in a tutoring session, which is a closer analog to a solitary student interacting with digital course materials, she might propose a more straightforward problem to help the student work it out:

Imagine you’re driving down a highway at night. A car is approaching from the other direction. Do their headlights seem to stay the same brightness as they get closer or does it seem to change?

It changes? OK, good. Now let’s go back to the original question about stars….

Educators can create that same pattern on our platform:

Cognitively, this approach helps the student learn by doing, which research tells us is an effective teaching practice. And it’s giving the student a puzzle to solve. It’s also communicating to the student, “I know you can figure this out yourself, and I care that you figure it out for yourself.” While sending that message through software is not the same as when delivered by a person, some software feedback strategies feel more humane and personal than others.

Technologically, this exercise is not fancy. There’s no AI. No Web3. No metaverse. It looks like a simple little feedback loop because that’s what it is. But educators use these little feedback loops all the time. Some are improvised, while others end up in the educators’ bags of tricks because they regularly address the same learning challenges with different students.

Making it Easier

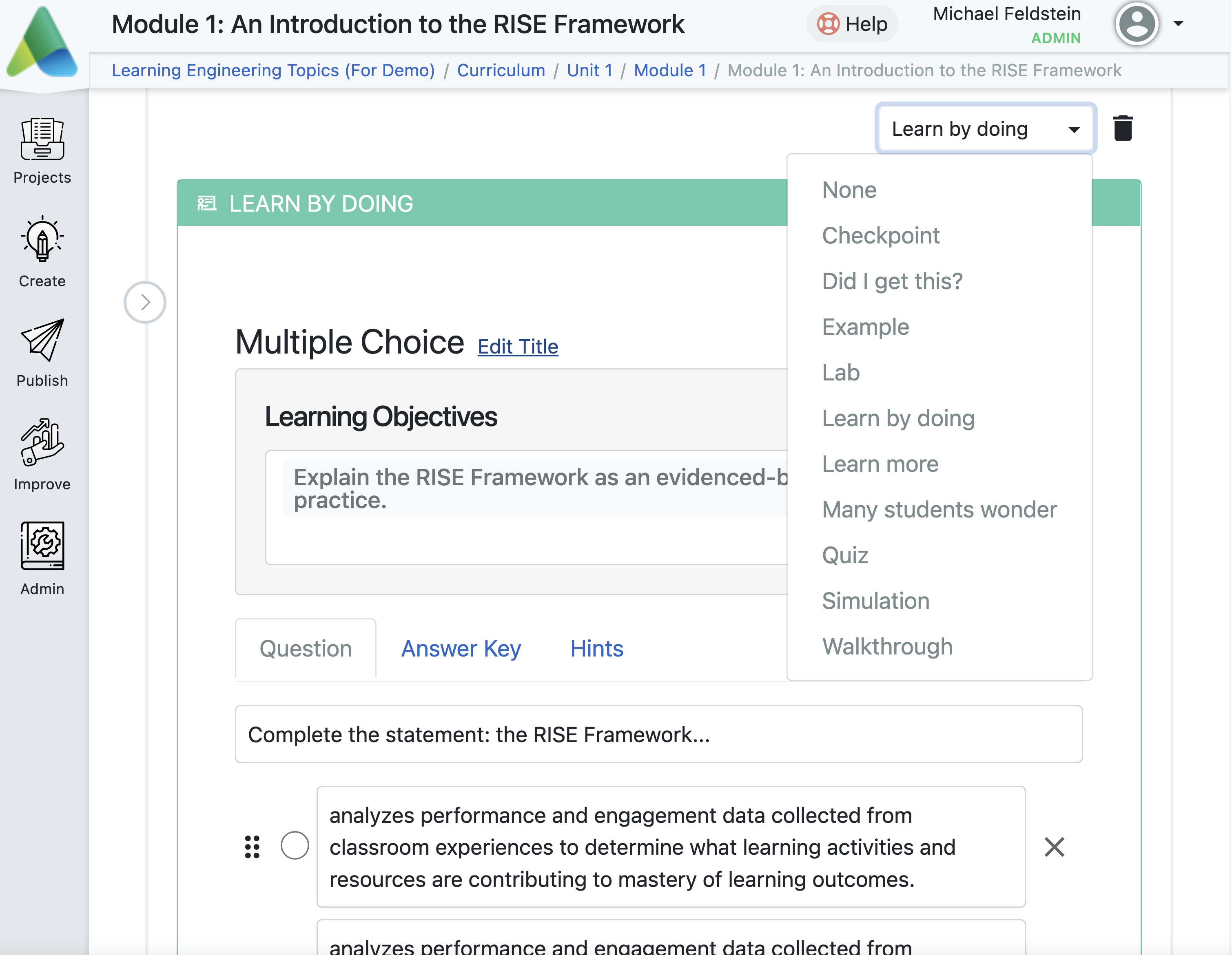

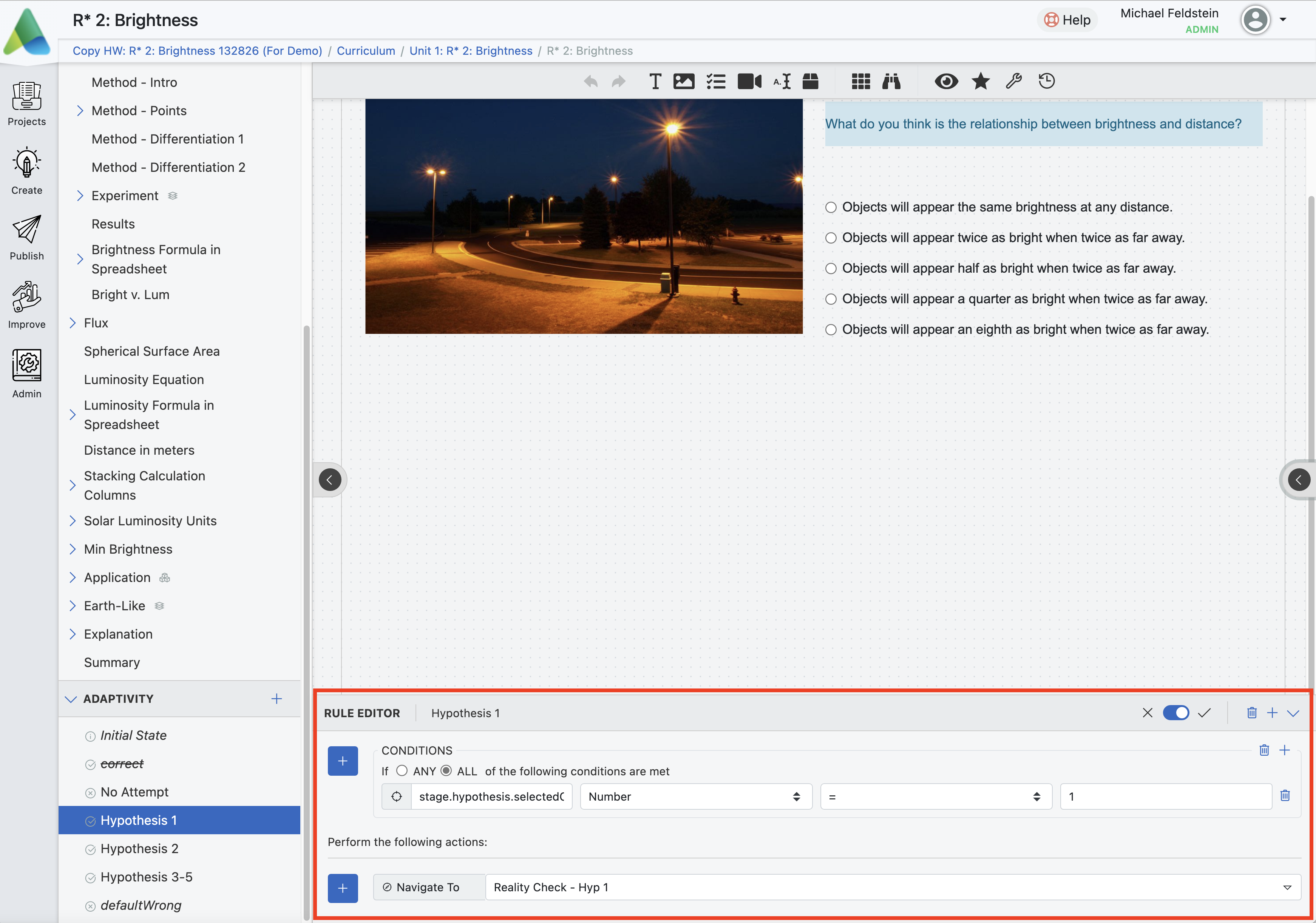

You may remember that in order to create the little feedback loop about the brightness of stars, we use an authoring interface that enables us to write branching rules:

This isn’t terribly complicated to learn how to do. It’s a low enough bar that publishers and some particularly motivated individual educators may craft learning experiences that would have been too hard or expensive to create and maintain without this tool. That said, the work required for this editor (as it exists today) may still be more than a lot of educators want to take on.

The simplicity challenge is one of the key barriers to creating real change. The “ask a simpler question” pattern is an example of a teaching move that many educators have and use. But they currently lack the tools and the time to bring such techniques into the technology-mediated parts of their teaching. We can change that.

Educators will be able to create much more engaging digital learning experiences when they can spend less time creating makeshift workarounds to static content and when incorporating their teaching skills into digital learning experiences is easy enough that they can actually focus on effective teaching. Argos shares a vision with its partners to make this possible.

Everything I’ve shown you so far is working software that Argos has in production with educators and students today. Now I will describe some of the capabilities we intend to build from here. For example, what if a learning designer could create a template and a little wizard that hides the rules behind a simple interface? We could add an “Ask a Simpler Question” item in the drop-down menu of the screen above. An educator who wants to use this pattern wouldn’t have to write any branching rules or know any logic. She would simply create an offshoot question page for incorrect answers to the multiple-choice question, guided by the software as she goes. The process could be very simple with no technical knowledge required. Users of the more complex adaptive authoring interface could create these templates and build up a library of them over time. Some could be shared, while others could be private or proprietary.

Doing the Work

One point of skepticism we hear about this approach is that educators won’t make time to do the work. It’s a reasonable concern to which we have two answers:

First, we don’t know what educators will do until we clear away the question of what they can do. Even if today’s educators had platforms that support such tweaks, they don’t have time to fine-tune because they’re busy managing working around their uneditable 60% solution in their textbook and searching for or creating the 20% that they need to have but don’t want to spend time on. So we haven’t had a fair test yet. That said, we at Argos have seen data from one of our partners showing that college educators spend an average of 8 hours a week during the semester finding and curating content for their courses. So educators are investing substantial time in creating content now. It’s just that most of the work is largely invisible.

Second, what if there was a middle ground between educators taking locked-down content and having to create it on their own. What if they could crowd-source improvement? Collaborate? Contribute bits? What if it wasn’t all or nothing?

Maybe most educators are unlikely to create an “Ask a Simpler Question” enhancement for every multiple choice question. But how about for one? Maybe they’d do it for one little exercise they created themselves and originally used in class. Or maybe they’d add it to an existing multiple-choice question in their adopted content. We believe educators will tweak their content because we know they’re already doing it.

Now, imagine if they could also share this change with other educators. Imagine if, say, 5,000 educators who all adopted the same “textbook” could share their changes and additions in a community. Or if the educators in a single university department could do the same within their group for a survey course. Imagine if those sharable changes were indexed to the text they were in, the chapter or unit or page they were in, and the learning objective they were linked to. Imagine if the platform could suggest community-shared changes relevant to the specific part of the curriculum that the educator is working on.

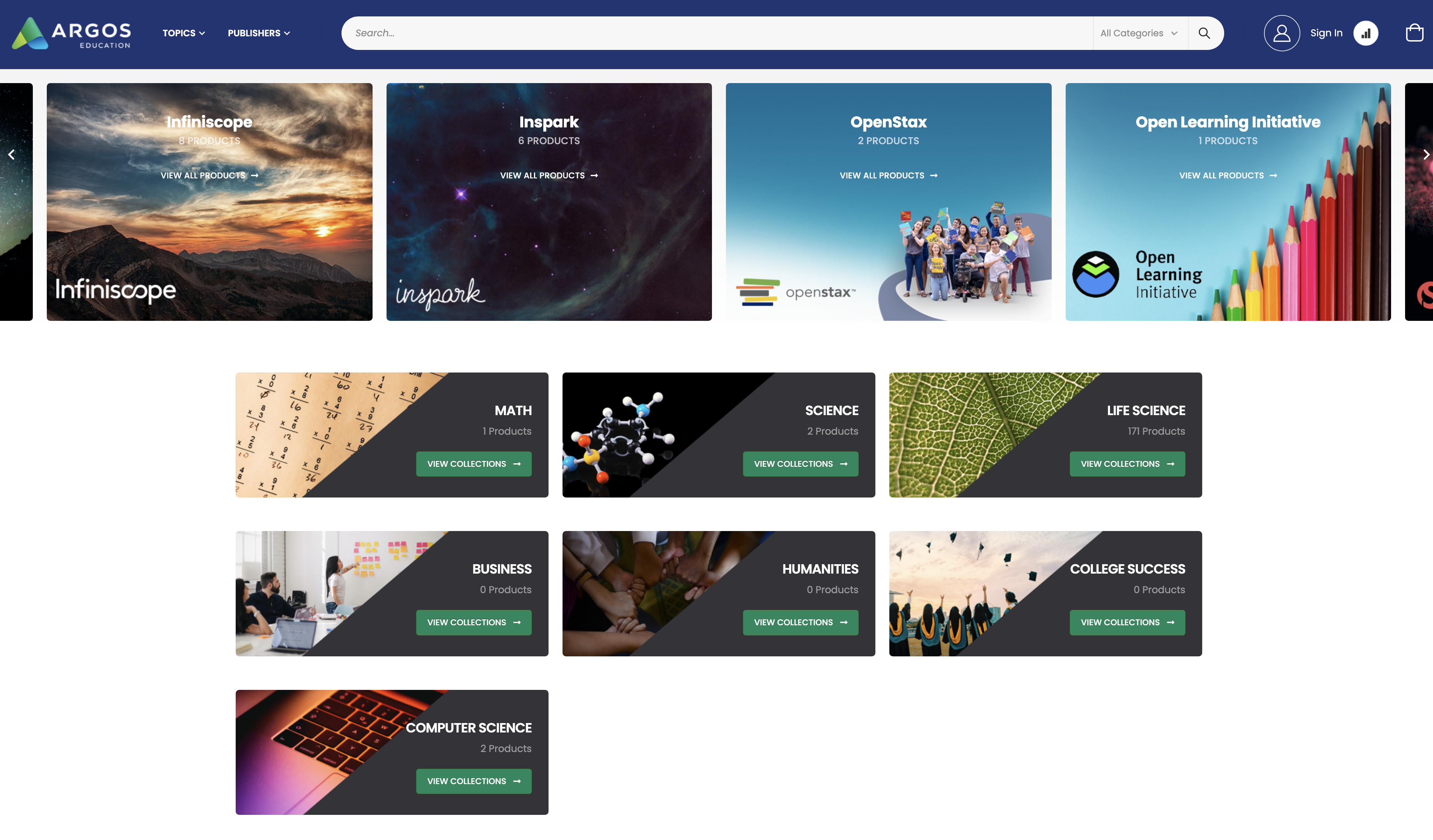

As our platform evolves, educators increasingly won’t have to work around the content they adopt anymore. They can start by picking a “textbook” that suits their needs reasonably well from a rich catalog of options. We already have a beta version of the storefront working:

Once educators pick their 60% solutions, they’ll be able to quickly fill in the 20% holes through easier and more accurate content searches and easier editing of the content. With that low-value work completed quickly and easily, they’ll have more time to invest in adding the special sauce to make their courses more engaging, effective, and well-tuned to the needs of their particular students.

We believe this approach will enable educators to focus less time wrestling with the technology and more time thinking about their teaching and their students.

Which sounds great. But can it actually lead to better educational content and more effective teaching? Our answer to both questions is yes. In my next two posts, I’ll take on each one in turn.